Despite over a billion US dollars for pilot initiatives by multilateral agencies and subsidies for private sector REDD+ projects and research programmes over the past 15 years, REDD+ has not fulfilled its promise of being a silver bullet in the fight against deforestation: global forest loss continues at alarming rates.

For developing countries, the Green Climate Fund is expected to become an important source of finance in the fight against climate change. Created in 2010 by the 194 countries that are party to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), it is the key vehicle for governments (mostly, but not exclusively, from the global North) to transfer the USD 100 billion annually by 2020 which they committed to under the UN's Paris Agreement on climate change.

The Fund does not implement projects itself. Instead, it provides funding for project proposals submitted by vetted entities: multilateral agencies like the UN Development Programme (UNDP), multilateral development banks, the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation (IFC), as well as national or regional agencies, including regional development banks or private banks and NGOs such as WWF or Conservation International. The majority of funding so far has been allocated to proposals from international agencies such as UNDP and multilateral development banks, with many projects and programmes focused on wind, solar and hydropower generation as well as energy savings.

More recently, the Green Climate Fund has begun to fund projects related to the restoration of so-called degraded ecosystems, including forests. A cause for concern is the emphasis that funded proposals put on tree planting and "ecosystem services" rather than on restoring ecological functions. Several projects also rely on fast-growing species such as eucalyptus in monoculture plantations. Particularly problematic is the Fund's move towards financing projects on Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+), the much-criticised mechanism which has dominated international forest policy discourse since 2005.

The announcement of the Green Climate Fund to scale up support, particularly for the most controversial aspect of REDD+, namely results-based payments and tradable carbon credits generated by private sector REDD+ projects, comes at an odd moment: Recognition is growing that REDD+ may actually be the wrong instrument for tackling drivers of large-scale deforestation, and even proponents of carbon offsets are beginning to raise questions about the future of offsetting. The Green Climate Fund's decision to scale up funding for REDD+ is all the more noteworthy considering the volume of funds flowing through the Fund, and a looming paucity of funding opportunities elsewhere. This combination could lead to the Fund becoming the only large long-term source of financing for REDD+, the international aviation industry being a further potential source.

Poor evidence that REDD+ actually reduces deforestation

Despite over a billion US dollars for pilot initiatives run by multilateral agencies such as the World Bank and subsidies for private sector REDD+ projects and research programmes over the past 15 years, REDD+ has not fulfilled its promise of being a silver bullet in the fight against deforestation: global forest loss continues at alarming rates and the carbon market, which was supposed to provide a large part of the funding for REDD, has not materialized, and is unlikely to do so in the foreseeable future (other than potentially through purchases from 2025 which would allow the international aviation industry to continue its unsustainable growth). Meanwhile, reports about land grabs and conflicts in relation with REDD+ project implementation are numerous while the number of supposedly successful REDD+ projects is regularly inflated by proponents. A report by the UK-based Rainforest Foundation expresses concern about the Green Climate Fund's approach to REDD+, noting that lessons are not being learnt from widely reported exclusion of local communities from REDD+ decision-making processes and a lack of independent oversight. Despite the sustained and mounting criticism of the concept and lack of evidence that REDD+ can deliver for either forest protection or climate mitigation, the Green Climate Fund approved its first REDD+ results-based payment in February 2019, providing USD 96.5 million for emissions allegedly reduced in Brazil through avoided deforestation in 2014 and 2015.

Paying for paper reductions?

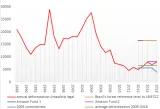

The funding request for “results-based REDD+ payment” approved at the 22nd Board meeting of the Green Climate Fund in February 2019 was submitted – on behalf of the Government of Brazil – by UNDP, one of the agencies vetted to submit requests. The payment received is for alleged emission reductions in 2014 and 2015. Alleged, because results-based REDD+ payments are awarded if the project proponent provides evidence that actual (emissions from) deforestation in the year for which payment is requested stayed below an agreed reference level. As with most such REDD+ payments, the evidence is disputed. In this case, the Fund agreed to pay as long as the government of Brazil kept emissions in 2014 and 2015 below the average of emissions caused by deforestation between 1996 and 2010 (see graph). This period includes the peak deforestation years in the Brazilian Amazon, resulting in a reference level for REDD+ payments that is well above actual deforestation rates in the last decade.

Brazilian Amazon deforestation of recent years could double and still generate “results-based” REDD+ payments under the reference level accepted by the Green Climate Fund in its February 2019 funding decision for the Fund's first results-based REDD+ payment.

(a) FREL Forest Reference Level the government of Brazil submitted to the UNFCCC. Basis for the 2019 Green Climate Fund results-based REDD+ payment: Average deforestation 1996-2010: 16,640km2 *

(b) Reference level Brazilian Amazon Fund 1 for payments 2011-2015. The Fund is managed by the Brazilian Development Bank BNDES and aims to raise donations for measures that reduce deforestation: Average deforestation 2001-2010: 16,540km2

(c) Reference level Brazilian Amazon Fund 2 for payments 2016-2020: Average deforestation 2006-2015: 8,150km2

(d) 2009 Brazilian government commitment to reduce deforestation in the Amazon by 80 percent by 2020, compared to 1996-2005 average deforestation: 3,925km2

Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. Impact of the reference level choice on emission reduction volume eligible for results-based REDD+ payment. Calculations based on PRODES program of the Brazilian Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais (INPE). http://www.inpe.br/noticias/noticia.php?Cod_Noticia=4957 *Payments are for tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2). Conversion from km2 of forest lost to tonnes of CO2 saved and other factors result in large uncertainties in forest carbon calculations.

In fact, the reference level against which the Green Climate Fund determined its payment "for results" is so inflated that even under the alarming increase in deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon since January 2019, the government of Brazil would still be eligible for results-based payment for emission reductions from deforestation.

As the graph above shows, a wide range of emission "reductions" can be calculated through the selective choice of reference level. One alternative reference level to the one chosen by the Green Climate Fund is the Brazilian government's voluntary commitment from 2009 (option d in Figure 1) to reduce deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon by 80 percent by 2020, compared to the average deforestation between 1996 and 2005. By this comparison, emissions from deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon were above the reference level in 2015 and the following years and just barely below in 2014 (see graph). Had the Green Climate Fund opted to use this 2009 commitment as a reference level, the 2015 levels of deforestation would have been above the reference level and the government of Brazil would not have qualified for results-based REDD+ payments for 2015. For 2014, only a small “result” would have been eligible for payment.

Brazil is often cited as having successfully reigned in Amazon deforestation since 2004, and the drop in deforestation between 2004 and 2012 is truly impressive. A rise in deforestation in recent years, however, also highlights the inability of REDD+ assistance to keep deforestation rates in Brazil at these lower levels: The large reduction in deforestation between 2004 and 2012 was possible through, among other actions, the implementation of measures against illegal clearing of forests which have since been largely replaced by policies prioritising REDD+ and payments for so-called ecosystem services. Deforestation rates have been increasing again in the past few years, with an alarming rise in the loss of Amazon forest in 2018.

Gearing up to subsidize private sector REDD+ investors?

Among the funding proposals in the Green Climate Fund pipeline is a request from the IFC for USD 72 million to set up a Multi-Country Forests Bond Programme. The IFC, the private sector arm of the World Bank, is one of the agencies vetted for submitting funding proposals to the Fund. Its proposed forests bond programme is modelled on an existing IFC bonds initiative which provides funding for a REDD+ project in Kenya.

Unlike the REDD+ proposals submitted by UNDP on behalf of the Brazilian and, at the 23rd GCF Board meeting, the Ecuadorian, government, the IFC REDD+ funding proposal to the Green Climate Fund would provide subsidies for private sector REDD+ initiatives and aim to generate tradable carbon credits. The IFC funding proposal is expected to provide financing for private sector REDD+ projects in three countries: the Democratic Republic of Congo, Madagascar and Peru.

The title of the project proposal is somewhat misleading because IFC intends to use the money raised through the issuance of the bonds not for forest conservation but to provide loans to a range of private sector projects related to climate change.

Where then is the link to forests and REDD+? Bond holders – the investors who provided the money that the IFC is giving out as loans in this programme – are entitled to annual payments for the investment they made. Under the Multi-Country Forests Bond Programme, they can choose to receive this payment either in cash or they can opt to be paid in carbon credits from private sector REDD+ projects or a mix of both. The IFC hopes that enough bond holders will want to receive their annual payment in REDD+ credits and that this will kick-start a carbon market for REDD+ credits and incentivize new private sector REDD+ projects. Preliminary project information suggests that the USD 72 million that the IFC hopes to receive from the Green Climate Fund will (a) provide upfront debt financing to new private sector REDD+ projects (USD 12 million); (b) enable the IFC (or an intermediary) to offer REDD+ carbon credits for even less than the USD 5 dollar going rate to the bond holders while guaranteeing a purchase price of USD 5 dollar to the private sector REDD+ projects (USD 52.5 million for a Liquidity Support Facility).

The only project currently selling REDD+ credits to the IFC which in turn has offered these to its forest bond holders is the Kasigau Corridor REDD+ project in Kenya. Reports show how the project has exacerbated historic inequalities by imposing the harshest restrictions on the most marginalised members of the community who contributed least to the climate crisis. Critics also note that the project is using an inflated reference level, resulting in an exaggeration of the avoided deforestation.

A report by the UK-based Rainforest Foundation which explores the likely consequences of the IFC funding proposal for community rights and REDD+ in the Democratic Republic of Congo concludes that "If the Kasigau Corridor REDD+ project is the exemplary model for selling forests bonds to fund REDD+ programmes, it is likely that funds from the Multi-Country Forests Bond programme will neither lead to substantial carbon savings nor greatly improved livelihoods of local communities."

Further reading:

- Heinrich Böll Stiftung (2019): Green Climate Fund and REDD+: Funding Paradigm Shift or Another Lost Decade for Forests and the Climate?

- Heinrich Böll Stiftung. Webdossier Green Climate Fund.

- Song, Lisa (2019): Another even more inconvenient truth. ProPublica.

- Rainforest Foundation UK (2019): Good Money After Bad? Risks and Opportunities for the Green Climate Fund in the Congo Basin Rainforests.

- Lang, C. (2019): Brazil’s funding proposal for REDD results-based payments to the Green Climate Fund would set a terrible precedent.

- ReCommon (2016): Mad Carbon Laundering. How the IFC subsidizes mining companies and failing REDD projects.